About Bird Dude Chip

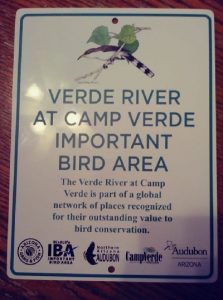

Camp Verde IBA

The sign to the left was given to me by Northern Arizona Audubon Society for my contribution to the Camp Verde IBA project.

How that came about was fate. The city of Camp Verde originated the project and hired a person to spearhead the project. Funding ran out before the project was completed and all the paper work was returned to the city. My daughter was interning in Camp Verde’s Economic Development and the project was dumped in her lap.

She brought the project home and asked for my help since she knew I had worked on the surveying the birds for the project. I then spent the next several days compiling data and documenting everything that could be documented. The project passed the first review. Below is the video shown at the Camp Verde IBA Dedication Ceremony. I’m interviewed but I’m not the one whose picture is on the video.

Bird Walk Guiding Experience

I have been birding the Verde Valley for the past 5 years. I currently lead field trips for the National Parks Service and Northern Arizona Audubon Society, as well as leading field trips in the annual Verde Valley Birding Festival and Sedona Hummingbird Festival.

Below is an interview with Yavapai Broadcasting on their series the Verde Valley Experience. It’s an hour show but I’ve clipped it to just my interview.

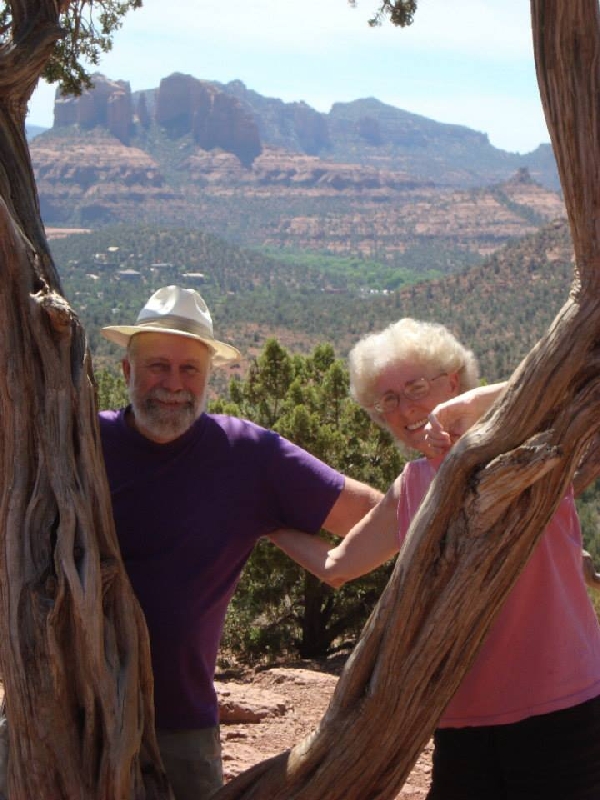

In My Natural Habitat

Birding Experience

I could tell you I’ve been birding for 30 years and that would be true, but not accurate.

I could tell you I’ve been birding for 30 years and that would be true, but not accurate.

The first time I went birding, or bird watching as it was called, was in the late 80’s. My wife Julie and I were at her extended family reunion just outside of Branson, Missouri and my sister in-law and her husband invited Julie and me to join them to go out and find some illusive tanager of some sort. I can speculate that it was probably a Summer Tanager.

I don’t know how they chose this particular place. We drove to a grassy area between corn crops and trees and walked down a an overgrown dirt road. The road split and we took an even more overgrown route crashing through knee-high grass. One of the women noticed we had bugs crawling all over us and we retreated to a bare spot in the less overgrown road.

Turns out the bugs were ticks–combination of the big brown wood ticks and and the itty-bitty red deer ticks that were known to cause lime disease. In a state of controlled panic we simultaneously stripped off our clothes and went about the task of searching each other and picking the bugs off each other. Believe me when I say, the fact that we were standing naked in front of God and everybody was not an issue.

Turns out the bugs were ticks–combination of the big brown wood ticks and and the itty-bitty red deer ticks that were known to cause lime disease. In a state of controlled panic we simultaneously stripped off our clothes and went about the task of searching each other and picking the bugs off each other. Believe me when I say, the fact that we were standing naked in front of God and everybody was not an issue.

In the end, we were bitten by only a single tick each, and in all cases they were wood ticks.

I don’t recall seeing a single bird.

Although it was not what anyone would call an auspicious first trip birding, I caught the birding tick bug. When I returned home, I dug out my 7×35 binoculars I bought in junior high school with paper route money and somehow acquired a copy of a 1977 edition of the Audubon Field Guide to North American Birds, and set about trying to find as many different species of birds as I could.

Although it was not what anyone would call an auspicious first trip birding, I caught the birding tick bug. When I returned home, I dug out my 7×35 binoculars I bought in junior high school with paper route money and somehow acquired a copy of a 1977 edition of the Audubon Field Guide to North American Birds, and set about trying to find as many different species of birds as I could.

At this point, I want to take s slight, but important detour, and describe what it is like birding with the 1977 edition of the Audubon Field Guide to North American Birds. The book is divided into two main sections: a glossy sections of photos so you can find a possible match to what you are seeing, and a normal paper section that list descriptions of birds based on the habitat they are found in. The idea is that you match the picture to what you are seeing, then go to the description to verify that your guess is plausible.

The glossy section is divided into fourteen groups:

Long-legged Waders

Gull-like Birds

Upright-Perching Water Birds

Duck-like Birds

Sandpiper-like Birds

Chicken-like Marsh Birds

Upland Ground Birds

Owls

Hawk-like Birds

Pigeon-like Birds

Swallow-like Birds

Tree-clinging Birds

Hummingbirds

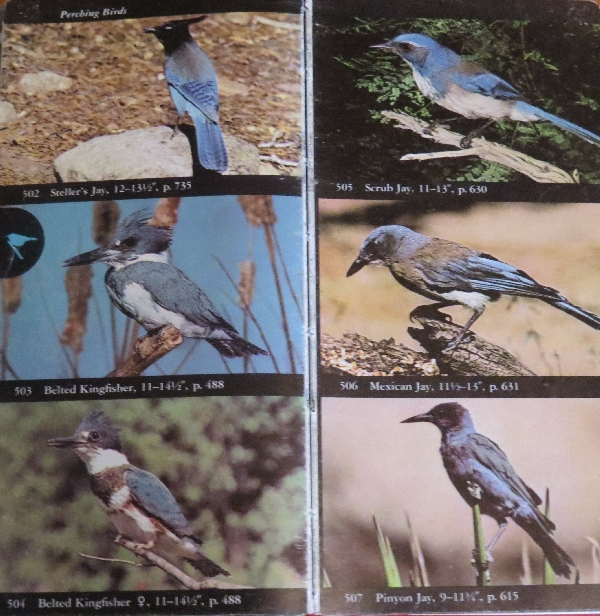

Perching Birds

Each group has an icon that shows the general outline of a bird that might be found in that group. Each of these groups is divided into smaller groups with the appropriate outline icons. For instance, Hawk-like Birds is divided into:

Caracaras

Vultures

Hawks

Falcons

Harriers

Kites

Eagles

Perching Birds are divided by color. So if you were to see a large blue bird, you would turn to the blue section and find which bird looks the most like what you see. One page has jays. On this page, the Scrub Jay has most blue and is pretty close the bird I see in my yard every day. On the other hand, the picture of the Mexican Jay is a dirty blue and brown bird that looks no Mexican Jay I’ve ever seen. The picture of the Pinon Jay is the worst of the lot and looks like a pointy-faced Brown-headed Cowbird.

The Western Tanager is found in the red section with the finches-House, Purple, and Cassin’s—and the Copper-tailed Trogon (now called Elegant Trogon).

Let’s take an example. You see a white and gray gull with orange legs and a red spot on the lower side of the bill sitting on a dock post in Southern California. According to the pictures, that could be a Herring Gull, a California Gull, a Glaucous-winged Gull. There are some size differences, but even though I was an accomplished carpenter at the time, I’ve never been able to actually get a tape-measure on a gull.

The next step is going to the page listing a description of each gull.

Three of the four are on sequential pages, the California Gull being located one hundred pages away. All of the birds shown were within the range listed by the field guide. The California Gull was said to have greenish legs, but when you go back to the pictures clearly shows them as orange. When you page back to the description, it also says there is a black spot on the bill. Luckily your bird is very cooperative and still there after five minutes of page rifling and there is no evidence of a black spot on the bill. So we can eliminate the California Gull.

The Herring Gull is described as having pink feet, so you go back to the picture and well, it could be sort of pinkish. The bird on the dock has pinkish feet. At this point you start looking around for something to use as a bookmark and find a candy wrapper which you tear in half. Both the Glaucous-winged Gull and the Western Gull are also described as having pink feet. The Glaucous-winged Gull is described as having a white “window” at the tip of the primaries—whatever that means. It was also says it has light brown or silvery eyes, while the other two birds have yellow eyes. The bird on the dock looks more yellow than light brown. So we can eliminate the Glaucous-winged Gull. This is a calculated risk.

The bird has been very cooperative as you are now 15 minutes into the id. You notice that the Herring Gull has a “yellow eyelid ringing the eye.” You see no eyelid of any kind so your bird must be a Western Gull. Knowing what I know now, probably 95% of gulls on the Southern California shore are Western Gulls, so you probably got it right.

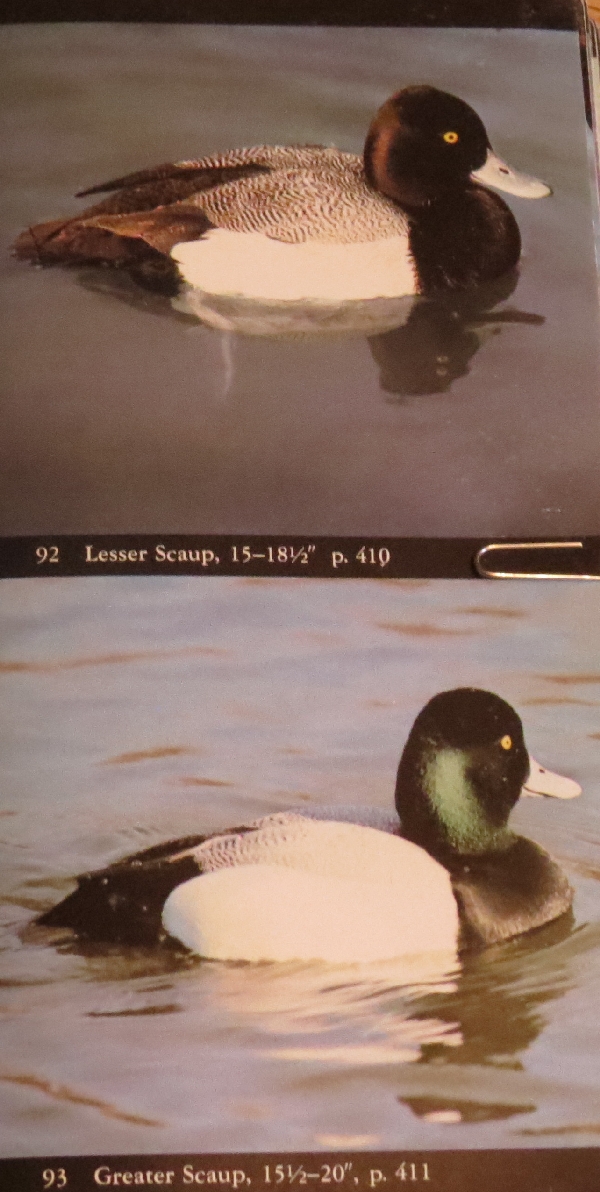

On the other hand, telling the difference between a Lesser Scaup and a Greater Scaup is quite easy as the Lesser Scaup has a black head while the Greater Scaup has a green head.

.

I returned to California armed with my Audubon Field Guide and 7×35 binoculars. It never occurred to me to look for guided trips or that anything like hotspots even existed. What I did is bird neighborhoods near me—which got me into diverse habitats as I took the binoculars with me to work repairing houses throughout the San Fernando Valley and Santa Monica Coast. When I traveled I birded State and National Parks and even found several bird sanctuaries.

I kept track of my birds by filling in the check list in the index, but I suspected I should do more so I included the date and location of my first sighting of each species. Looking back, I probably identified most of my birds correctly. However later when I filled in my historical sightings into eBird, a reviewer questioned my 1990 sighting of a Yellow-billed Loon in Arcata Bird Sactuary and wanted more details.

“Heck,” I replied, “That was thirty years ago. It could have been a Yellow-billed Magpie for all I know.”

When I moved to Pennsylvania I birded at every place we stopped as we crossed the country. When we visited Julie’s parents cottage in Wisconsin, I birded the northern lakes. However, when I got to Pennsylvania, I got caught up first in graduate studies, then in our vitamin catalog/Internet business. And we had kids. My birding for those 25 years was mostly backyard birding.

My transition from being a bumbling birder to a more serious birder came as a result of three separate evolutions. When I arrived in Arizona, I was looking for a way to get out into nature and get a modicum of exercise. Reviving my bird watching hobby seemed to be the perfect way to accomplish these goals. Through a local publication, I learned of bird walk sponsored by the National Parks Service.

On the walk, I pointed out a Rufous-sided Towhee. Jeff Tanner, the leader, looked at me with an odd look. I showed him the picture I had in my book. He told me that the species had been split in the early 1990’s and that what I knew as a Rufous-sided Towhee was now a Eastern Towhee, and what I had seen was a Spotted Towhee. He showed me a picture in Sibley’s Birds West. I was so impressed with the book, I immediately when on eBay found a older Sibley’s Guide. The Sibley’s Guide streamlined my identification process by magnitudes.

On the walk, I pointed out a Rufous-sided Towhee. Jeff Tanner, the leader, looked at me with an odd look. I showed him the picture I had in my book. He told me that the species had been split in the early 1990’s and that what I knew as a Rufous-sided Towhee was now a Eastern Towhee, and what I had seen was a Spotted Towhee. He showed me a picture in Sibley’s Birds West. I was so impressed with the book, I immediately when on eBay found a older Sibley’s Guide. The Sibley’s Guide streamlined my identification process by magnitudes.

The second evolution was when I upgraded my binoculars to Nikon Acculon 8×42 binoculars. I could actually focus these new binoculars. I found out later, the 7×35 binoculars had developed a loose prism.

The third evolution occurred when at Page Springs Fish Hatchery, I ran into a guy carrying a cannon—actually a Cannon camera with a lens that looked like a cannon. This man was Sam Hough. He was also wearing binoculars that was hanging down to his waist. I saw him again at Lake Montezuma and he convinced me to post my sightings on eBird.

A few weeks later, I posted a checklist to my yard list. On this list were among other birds, a Mexican Jay, an Arizona Woodpecker, and a Magnificent Hummingbird. I got a call, from among others, Rich Armstrong, questioning my sanity. What had happened is that I was posting from Madera Canyon where such birds were common.

A few weeks later, I posted a checklist to my yard list. On this list were among other birds, a Mexican Jay, an Arizona Woodpecker, and a Magnificent Hummingbird. I got a call, from among others, Rich Armstrong, questioning my sanity. What had happened is that I was posting from Madera Canyon where such birds were common.

Somehow in my fumbling with the eBird program, the location of my report has reverted to my house, the first address on my list. A weeks later, I met Rich Armstrong at the Verde Valley Birding Festival and we laughed about the fiasco. And this was my introduction into the very supportive Verde Valley birding community.

All that is to say, I’ve been a “serious” birder for five years.